Feral Swine: USDA Monitors World’s Worst Invasive Alien Species

Jennifer Shike

May 6, 2019

Feral swine don’t recognize boundaries. They’re devastating to U.S. agriculture. Some say they’re the world’s worst invasive alien species. And sadly, this problem isn’t going away.

The USDA estimates the feral swine population in the United States is spreading at a rate of 55 to 70 miles per hour…in the back of trucks and trailers. Feral swine typically do not move to new areas through natural dispersion. Instead, humans play a significant role in their movement.

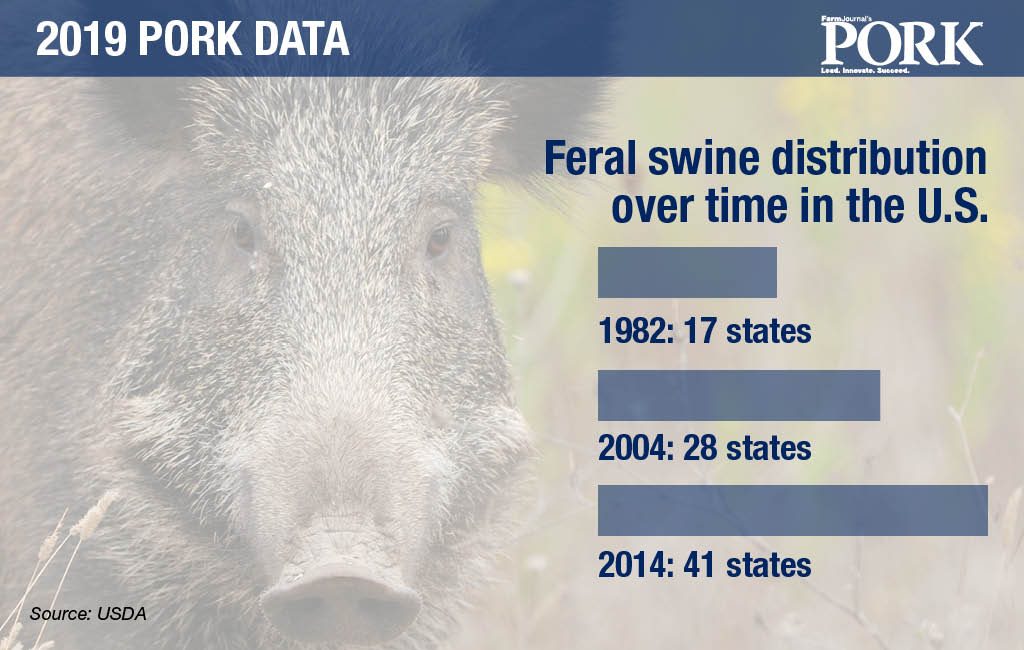

As the feral swine population grows, many of us are feeling the consequences, especially in the southern and southeastern United States. Feral swine have been in the United States for centuries. In the 1500s, when early explorers came to the country, they released pigs as they explored so they’d have a food source when they returned. Most recently, in the 1970s and 1980s, the United States experienced an explosion of feral swine. Not only did the number of pigs grow, but they also began appearing in more states.

Dale Nolte, program manager for the USDA APHIS National Feral Swine Damage Management Program, says feral swine have spread to 41 states in 2014, when Congress allocated funds to address the growing feral swine problem in the United States.

“We initially believed feral swine caused $1.5 billion in damage a year in the U.S., but now we think that number is closer to $2.5 billion, not accounting for the environmental damage that is hard to assign a dollar value,” Nolte says. “I’ve worked with a lot of different species, and they normally cause damage in a certain area. But not feral swine – they cause damage across every sector.”

ASF monitoring

Nolte, based out of Fort Collins, Colo., recently spoke at the African Swine Fever (ASF) Forum in Ottawa, Canada, about the national feral swine program that encompasses operations, research, disease monitoring, communication, regulation and evaluation and monitoring.

“We don’t have ASF in the U.S., but everyone wants to be prepared if it does emerge,” he says. “Our group is charged with maintaining awareness of the wild pig population in the U.S. If we were to get ASF in our wild pig population, it would be a huge problem and make it harder to eliminate the disease.”

Feral swine can transmit pathogens to domestic pigs and vector more than 20 diseases that scientists know of at this time.

“Our group is maintaining an awareness of mortality events in feral swine,” Nolte says. “ASF generally results in death fairly quickly. If ASF does get into our wild pig population, we’ll see dead pigs. We are monitoring and responding to reports of dead pigs to determine probable cause. If there is no obvious explanation, we report those cases to Veterinary Services, who decides if they will send in a foreign animal disease investigation team.”

Biosecurity remains the swine industry’s primary defense.

“Everyone’s hope is we are preparing for something that will never happen,” he says. “I don’t want to raise an alarm with feral swine and ASF, but it’s good to be prepared.”

Nolte says the ASF Forum provided opportunities to connect with Canadian officials about working together to establish better collaborations.

“We’ve been working closely with officials in Mexico monitoring the Mexican border for the past few years to get a better understanding of feral swine movement across the border, primarily into Texas,” Nolte says.

Farm Bill funding

In the 2018 Farm Bill, $75 million was designated to establish a “feral swine eradication and control pilot program” over the next five years to help landowners with trapping and to use modern technology to control feral hogs. The $75 million will be a 50-50 split between NRCS (for on-farm trapping and technology related to capturing and confining feral swine) and APHIS (for operational removal of feral swine).

“Our intent is to work on joint projects together – we are laying framework now for what those projects will consist of and identifying areas where feral swine populations are high,” Nolte says. “Our focus will be to reduce agricultural damage from feral swine.”

Program announcements will likely take place in June, he adds.

How can you help?

When it comes to pig removal, Nolte says state wildlife agencies have jurisdiction. But Nolte’s team helps develop strategies to remove animals, generally done by trapping or through their aerial program.

“In Texas, for example, the problems are overwhelming,” he says. “We don’t have resources to assist everyone immediately. But state agencies and wildlife service state directors help us identify where to focus.”

If you are in areas where feral swine are rare, report sightings of pigs – dead or alive – so authorities can monitor and remove animals if possible.

“Don’t move the pigs,” Nolte says. “We believe a lot of distribution around the country is due to people moving them from where they’ve been for some time into new areas. Feral swine may provide a recreational opportunity through hunting, but they are such a detrimental animal – not just to agriculture.”

It’s also important to be aware of human health risks from feral swine interaction, he adds. ASF is not a zoonotic threat, but feral swine do carry several zoonotic diseases such as hepatitis, leptospirosis, brucellosis, and more that can be passed on to people.

“People have suffered severe consequences because of encounters with feral pigs,” Nolte says. “It’s important to know there are risks.”

Story Source and photo credit from:

https://www.porkbusiness.com/news/hog-production/feral-swine-usda-monitors-worlds-worst-invasive-alien-species